\\\\(

\nonumber

\newcommand{\bevisslut}{$\blacksquare$}

\newenvironment{matr}[1]{\hspace{-.8mm}\begin{bmatrix}\hspace{-1mm}\begin{array}{#1}}{\end{array}\hspace{-1mm}\end{bmatrix}\hspace{-.8mm}}

\newcommand{\transp}{\hspace{-.6mm}^{\top}}

\newcommand{\maengde}[2]{\left\lbrace \hspace{-1mm} \begin{array}{c|c} #1 & #2 \end{array} \hspace{-1mm} \right\rbrace}

\newenvironment{eqnalign}[1]{\begin{equation}\begin{array}{#1}}{\end{array}\end{equation}}

\newcommand{\eqnl}{}

\newcommand{\matind}[3]{{_\mathrm{#1}\mathbf{#2}_\mathrm{#3}}}

\newcommand{\vekind}[2]{{_\mathrm{#1}\mathbf{#2}}}

\newcommand{\jac}[2]{{\mathrm{Jacobi}_\mathbf{#1} (#2)}}

\newcommand{\diver}[2]{{\mathrm{div}\mathbf{#1} (#2)}}

\newcommand{\rot}[1]{{\mathbf{rot}\mathbf{(#1)}}}

\newcommand{\am}{\mathrm{am}}

\newcommand{\gm}{\mathrm{gm}}

\newcommand{\E}{\mathrm{E}}

\newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}

\newcommand{\mU}{\mathbf{U}}

\newcommand{\mA}{\mathbf{A}}

\newcommand{\mB}{\mathbf{B}}

\newcommand{\mC}{\mathbf{C}}

\newcommand{\mD}{\mathbf{D}}

\newcommand{\mE}{\mathbf{E}}

\newcommand{\mF}{\mathbf{F}}

\newcommand{\mK}{\mathbf{K}}

\newcommand{\mI}{\mathbf{I}}

\newcommand{\mM}{\mathbf{M}}

\newcommand{\mN}{\mathbf{N}}

\newcommand{\mQ}{\mathbf{Q}}

\newcommand{\mT}{\mathbf{T}}

\newcommand{\mV}{\mathbf{V}}

\newcommand{\mW}{\mathbf{W}}

\newcommand{\mX}{\mathbf{X}}

\newcommand{\ma}{\mathbf{a}}

\newcommand{\mb}{\mathbf{b}}

\newcommand{\mc}{\mathbf{c}}

\newcommand{\md}{\mathbf{d}}

\newcommand{\me}{\mathbf{e}}

\newcommand{\mn}{\mathbf{n}}

\newcommand{\mr}{\mathbf{r}}

\newcommand{\mv}{\mathbf{v}}

\newcommand{\mw}{\mathbf{w}}

\newcommand{\mx}{\mathbf{x}}

\newcommand{\mxb}{\mathbf{x_{bet}}}

\newcommand{\my}{\mathbf{y}}

\newcommand{\mz}{\mathbf{z}}

\newcommand{\reel}{\mathbb{R}}

\newcommand{\mL}{\bm{\Lambda}}

\newcommand{\mnul}{\mathbf{0}}

\newcommand{\trap}[1]{\mathrm{trap}(#1)}

\newcommand{\Det}{\operatorname{Det}}

\newcommand{\adj}{\operatorname{adj}}

\newcommand{\Ar}{\operatorname{Areal}}

\newcommand{\Vol}{\operatorname{Vol}}

\newcommand{\Rum}{\operatorname{Rum}}

\newcommand{\diag}{\operatorname{\bf{diag}}}

\newcommand{\bidiag}{\operatorname{\bf{bidiag}}}

\newcommand{\spanVec}[1]{\mathrm{span}{#1}}

\newcommand{\Div}{\operatorname{Div}}

\newcommand{\Rot}{\operatorname{\mathbf{Rot}}}

\newcommand{\Jac}{\operatorname{Jacobi}}

\newcommand{\Tan}{\operatorname{Tan}}

\newcommand{\Ort}{\operatorname{Ort}}

\newcommand{\Flux}{\operatorname{Flux}}

\newcommand{\Cmass}{\operatorname{Cm}}

\newcommand{\Imom}{\operatorname{Im}}

\newcommand{\Pmom}{\operatorname{Pm}}

\newcommand{\IS}{\operatorname{I}}

\newcommand{\IIS}{\operatorname{II}}

\newcommand{\IIIS}{\operatorname{III}}

\newcommand{\Le}{\operatorname{L}}

\newcommand{\app}{\operatorname{app}}

\newcommand{\M}{\operatorname{M}}

\newcommand{\re}{\mathrm{Re}}

\newcommand{\im}{\mathrm{Im}}

\newcommand{\compl}{\mathbb{C}}

\newcommand{\e}{\mathrm{e}}

\\\\)

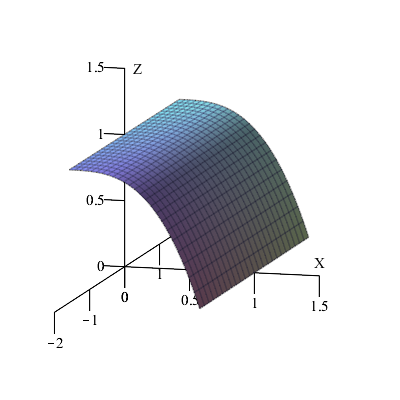

Exercise 1: Flux through an Open vs. Closed Surface A function $\,h:\reel^2 \rightarrow \reel\,$ is given by the expression

$$\,h(x,y)=1-x^3\,.$$

We consider a rectangle in the $(x,y)$ plane that is determined by $\,0\leq x\leq 1\,$ and $\,-\frac{\pi}2\leq y\leq \frac{\pi}2\,.$ Let the surface $\,\mathcal F\,$ be the part of the graph of $\,h\,$ that is located vertically above the rectangle.

A

Provide a parametric representation of $\mathcal F\,.$

Show hint

Note that $\mathcal F$ is a graph surface.

Show answer

$$\mathbf s(u,v)=(u,v,1-u^3)\quad\text{where}\quad u\in \left[0,1\right]\,,\,v\in \left[-\frac{\pi}2,\frac{\pi}2\right]$$

A vector field $\,\mV\,$ is given by

$$\,\displaystyle{\mV(x,y,z)=\begin{matr}{c}xz\newline x\cos(y)\newline 3x^2\end{matr}\,.}$$

B

Compute the flux of $\mV$ through $\mathcal F\,.$

Show hint

First find the integrand for the flux integral. It is a dot product.

Show hint

State from the parametric representation the normal vector $\mathbf N\,.$ Then the integrand is

$$\mV(\mathbf s(u,v))\cdot \mathbf N\,.$$

Show hint

The integrand is

$$-3u^6+3u^3+3u^2\,.$$

Show answer

$$\displaystyle{\int_{\mathcal F}}\mV\cdot \mathbf n\,\mathrm du=\frac{37}{28}\,\pi$$

Now let $\Omega$ denote a solid spatial region located vertically between the rectangle in the $(x,y)$ plane and $\mathcal F\,.$

C

Determine a parametric representation of $\Omega\,.$

Show hint

Probably you can use the parametric representation you made for $\mathcal F\,$ by adjusting the third coordinate a bit.

Show answer

$$\mr(u,v,w)=(u,v,w(1-u^3))\,\quad\,,\,u\in \left[0,1\right]\,,\,v\in \left[-\frac{\pi}2,\frac{\pi}2\right]\,,\,w\in \left[0,1\right]$$

D

Use Gauss’ Theorem to determine the flux of $\mV$ out through the surface of $\Omega\,.$

Show hint

Actually the surface of $\Omega$ consist of 5 parts. The good thing about Gauss’ Theorem is that we only need one integral, but it is a volume integral.

Show hint

You must compute the volume integral of the divergence of $\mV$ through $\Omega\,.$ Find the integrand, which is

$$\mathrm{Div}(\mV)(\mr(u,v,w))\cdot\mathrm{Jacobian}_{\mathbf r }(u,v,w)\,,$$

and determine the triple integral, possibly using Maple.

Show hint

The integrand is

$$\,u^6w-2u^3w+w+u^4\sin(v)-u\sin(v)\,.$$

Show answer

$$\,\displaystyle{\frac{9}{28}}\,\pi$$

Exercise 2: 12 Fluxes of Fields with Constant Divergence A spatial region $\Omega_1$ is a solid unit sphere centred at the origin, and another spatial region $\Omega_2$ is given by the parametric representation

$$\mr(u,v,w)=(u\cos(v),u\sin(v),u^2+w(1-u^2)\,)\,,$$

$$u\in \left[0,1\right]\,,v\in \left[-\pi,\pi\right]\,,w\in \left[0,1\right].$$

Their surfaces $\partial \Omega_1$ and $\partial \Omega_2$ are oriented with outwards-pointing unit normal vectors. In addition we are given the following six vector fields:

$$\begin{align*}

\mV_1(x,y,z)&=(1,2,3)\newline

\mV_2(x,y,z)&=\left(-x,\frac y2,-\frac z3\right)\newline

\mV_3(x,y,z)&=(x-yz,-2y+xz^2,3z+yx^3)\newline

\mV_4(x,y,z)&=(k_1,k_2,k_3)\newline

\mV_5(x,y,z)&=(y-x^3,3x^2y,25+10z)\newline

\mV_6(x,y,z)&=(2xz-2xy-z,z^3+y^2,-z^2)

\end{align*}$$

A

Compute the 12 fluxes

$$\mathrm{Flux}(\mV_i,\,\partial\Omega_j)\,,\,i=1..6\,,\,j=1..2\,.$$

Show hint

Compute the volume of $\Omega_1$ and $\Omega_2\,$ and then the divergence of each of the six vector fields.

Show hint

$$\mathrm{Vol}(\Omega_1)=\frac43\pi$$

$$\mathrm{Vol}(\Omega_2)=\frac {\pi}2$$

From Gauss’ Theorem it follows that the fluxes are found by multiplication of the volume with the divergence.

Exercise 3: Gauss’ Theorem and Divergence A parametrized spatial region $\Omega_{\mathbf r}$ in $(x,y,z)$ space has the parametric representation

$$\mr(u,v,w)=(u\cos(v),u\sin(v),w)\,,\,\,u\in\left[0,2\right]\,,\,\,v\in\left[0,\frac{\pi}{2}\right]\,,\,\,w\in\left[0,5\right]\,.$$

A

$\Omega_{\mathbf r}$ is a parametrization of a simple geometric object. Describe which, and find its volume by elementary geometric means.

Show answer

This is a quarter of a cylinder of revolution with a bottom radius of $2$ and a height of $5$ . The volume is thus

$$\mathrm{Vol(\Omega_{\mr})}=\frac14\pi \mathrm{radius}^2h=\,5\pi\,.$$

We are about the vector fields $\mU$ and $\mV$ informed that:

$$\mathrm{Div}(\mU)(x,y,z)=\pi\,\,\,\,\mathrm{and}\,\,\,\,\mathrm{Div}(\mV)(x,y,z)=yz\,.$$

B

Determine the fluxes

$$\,\displaystyle{\int_{\partial \Omega_{\mathbf r}}\mU\cdot \mathbf n_{\partial \Omega_{\mathbf r}}\,\mathrm du}\,\,\,\,\textrm{and}\,\,\,\,

\,\displaystyle{\int_{\partial\Omega_{\mathbf r}}\mV\cdot \mathbf n_{\partial \Omega_{\mathbf r}}\,\mathrm du}\,.$$

Show answer

$$\,\displaystyle{\int_{\partial \Omega_{\mathbf r}}\mU\cdot \mathbf n\,\mathrm du}=5\pi^2\,$$

$$\,\displaystyle{\int_{\partial\Omega_{\mathbf r}}\mV\cdot \mathbf n\,\mathrm du}=\frac{100}{3}$$

Exercise 4: Gauss’ Theorem Applied on an Open Surface! We are given the vector field

$$\mV(x,y,z)=(\e^y+\cos(yz),\e^z+\sin (xz),x^2z^2),\, (x,y,z)\in\reel^3$$

together with a hemi-spherical surface $F$ given by

$$x^2+y^2+z^2-4z=0\,\,\mathrm{and}\,\,z\leq 2\,.$$

A

Draw a sketch of $F$ using pen and paper.

Show hint

Complete the square to remove the single term from the equation. You’ll then see that we are dealing with the bottom half of a spherical shell centred at $(0,0,2)$ with a radius of $2$ .

$F$ is thought to be oriented with a unit normal vector field with negative $z$ coordinate. We wish to determine the flux though $F,$ but it turns out to be rather difficult to integrate over the surface $F\,$ since the vector field is a bit complicated. On the other hand it is not difficult to compute $\mathrm{Div}(\mV)(x,y,z)\,.$ So let us tune the problem to be solvable via Gauss’ Theorem. We will start by integrating the divergence of $\mV$ through the solid hemisphere $\Omega$ that fills $F$ .

B

Compute the flux of $\mV$ out through the surface $\partial \Omega$ of $\Omega$ by computing

$$\int_{\Omega}\mathrm{Div} (\mV)\, \mathrm d\mu\,.$$

Show hint

This is a usual volume integral with a Jacobian and all.

Show hint

Create a parametric representation of the solid sphere and compute its corresponding Jacobian. Then restrict the vector field to this parametrization.

Show hint

A possible parametrization is

$$\mr(u,v,w)=(u\sin(v)\cos(w), u\sin(v)\sin(w), u\cos(v)+2)$$

with fitting parameter intervals.

The Jacobian becomes $\,u^2\sin(v)\,.$

We have now computed the flux through a closed surface. But the hemi-spherical surface $F$ is open at the top! We have thus included the flux through the top even though it shouldn’t have been included - let’s find it and subtract it away.

C

Find a parametric representation of the circular disc that can cover the top of the hemisphere.

Show answer

$$\mathbf s(u,w)=(u\cos (w),u\sin(w),2),\quad u\in\left[ 0,2\right] ,\, w\in\left[0,2\pi\right] $$

D

Compute the flux through the circular disc.

Show hint

$$N_{\mathbf s}=(0,0,u)$$

E

Now state the flux through $F$ .

Show hint

Subtract the flux through the circular disc at the top from the total flux through the closed surface that was found via the divergence integration.

Show answer

$$\mathrm{Flux}(\mV,F)=-\frac{64\pi}{15}$$

We are given the vector field

$$\mV(x,y,z)=(x^3+xy^2,4yz^2-2x^2y,-z^3)$$

and the solid region

$$\Omega=\left\{ (x,y,z)\,|\, x^2+y^2+z^2\leq a^2\right\}\,.$$

A

Compute the flux of $\mV$ out through the surface $\partial \Omega$ of $\Omega\,.$

Show hint

$$\mathrm{Div}(\mV)(x_0,y_0,z_0)=x^2+y^2+z^2$$

Show answer

$$\mathrm{Flux}(\mV,\Omega)= \int_{-\pi}^{\pi}\int_0^{pi}\int_0^a\, u^4\,\sin (v)\,\mathrm du\,\mathrm dv\,\mathrm dw=\frac{4a^5\pi}{5}$$

We are given the vector field $\mV(x,y,z)=(2x,3y,-z)$ and the solid region

$$\Omega=\left\{ (x,y,z)\,|\,\left( \frac{x}{a}\right) ^2+\left( \frac{y}{b}\right) ^2+\left( \frac{z}{c}\right) ^2\leq 1\right\}\,.$$

A

Determine the flux of $\mV$ out through the surface $\partial \Omega$ of $\Omega\,.$

Show hint

$$\mathrm{Div}(\mV)(x_0,y_0,z_0)=4$$

Show hint

What is the consequence of the divergence being constant?

Show hint

$\Omega$ is a solid ellipsoid.

Show answer

$$\mathrm{Flux}(\mV,\Omega)= \mathrm{Div}(\mV)(x_0,y_0,z_0)\cdot\Vol_\Omega=\frac{16\pi}{3}abc$$